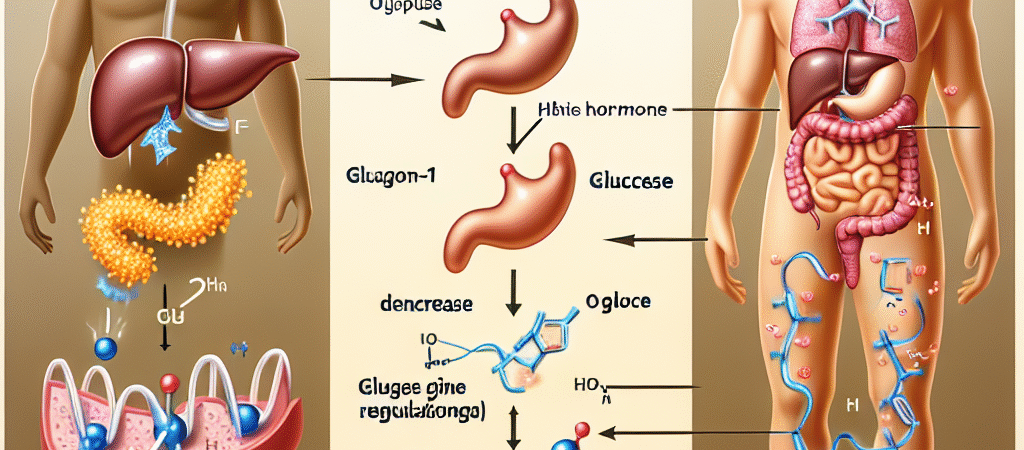

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) is a hormone that helps coordinate the body’s response to meals. It belongs to a family of hormones called incretins, which are secreted by the gut in response to nutrient intake and influence insulin release and glucose metabolism. GLP-1 is produced primarily by L cells scattered along the lining of the small intestine and, to a lesser extent, in the colon. In humans, the active form is GLP-1(7-36) amide, and another circulating form is GLP-1(7-37), with both rapidly inactivated by circulating enzymes.

How GLP-1 regulates glucose

1) Insulin secretion that depends on blood glucose

– GLP-1 acts on receptors on pancreatic beta cells (GLP-1 receptors are G protein–coupled receptors that raise cAMP inside the cell).

– When blood glucose is elevated, GLP-1 enhances glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. Importantly, this effect is glucose-dependent: as blood glucose falls toward normal levels, GLP-1’s stimulation of insulin release wanes. This helps reduce the risk of hypoglycemia compared with other insulin-releasing therapies.

2) Suppression of glucagon

– GLP-1 also reduces glucagon secretion from pancreatic alpha cells, especially when glucose is high after a meal. Lower glucagon helps decrease hepatic glucose production, contributing to lower postprandial (after-meal) blood glucose levels.

3) Slowing of gastric emptying

– GLP-1 slows the movement of food from the stomach into the small intestine. This blunts the rate at which glucose enters the bloodstream after eating, dampening spikes in postprandial glucose.

4) Appetite and weight regulation

– GLP-1 acts on the brain, particularly areas involved in appetite and satiety, to reduce hunger. This central effect can lead to lower energy intake and modest weight loss, which can further improve glucose control in people with insulin resistance or type 2 diabetes.

5) Other tissues and effects

– GLP-1 receptors are present in various tissues, including the brain, gut, heart, and blood vessels. Through these sites, GLP-1 can influence cardiovascular function and other metabolic processes. The full spectrum of GLP-1’s actions is complex and continues to be studied, but the combined effects on insulin, glucagon, gastric emptying, and appetite are central to its role in glucose regulation.

What makes GLP-1 unique among incretins

– Incretin effect: When glucose is eaten (oral glucose), the gut releases GLP-1 (and other incretins), which boosts insulin secretion more than when the same amount of glucose is given intravenously. This illustrates how the gut’s hormonal response helps regulate post-meal blood sugar.

– Rapid inactivation: Native GLP-1 is quickly broken down by the enzyme dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4), giving it a very short circulating half-life. Because of this, therapies that mimic or prolong GLP-1 action have been developed.

Therapeutic implications: how medicine uses GLP-1

1) GLP-1 receptor agonists

– These drugs are stable forms of GLP-1 or GLP-1-like molecules that resist rapid breakdown, providing longer-lasting activity. They mimic the natural actions of GLP-1: increased glucose-dependent insulin release, reduced glucagon, slower gastric emptying, and appetite suppression.

– Examples include weekly or daily injections such as dulaglutide, semaglutide, liraglutide, and exenatide. There is also an oral form of semaglutide available in some regions.

– Benefits observed in people with type 2 diabetes include improved glycemic control and, for many, weight loss and potential cardiovascular benefits. Common side effects are gastrointestinal (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea), especially when starting therapy.

2) DPP-4 inhibitors

– DPP-4 inhibitors (for example, sitagliptin, linagliptin, alogliptin) work by blocking the enzyme that rapidly degrades GLP-1, thereby increasing the levels and activity of endogenous GLP-1.

– These therapies generally have a lower risk of weight loss and less GI side effects compared with GLP-1 receptor agonists, but are often less potent in lowering A1C for some patients. They also carry a low risk of hypoglycemia when used alone.

3) Clinical considerations

– GLP-1–based therapies are particularly useful in type 2 diabetes when weight loss is desirable or when hypoglycemia risk needs to be minimized.

– They may have additional cardiovascular or renal benefits demonstrated in some large trials, especially with certain long-acting GLP-1 receptor agonists.

– Side effects often limit uptake; GI symptoms typically improve over time. There is ongoing monitoring for rare adverse events, and individuals with a history of certain conditions should discuss risks with a clinician.

Putting GLP-1 into the bigger picture of glucose regulation

– After a meal, GLP-1 helps ensure that the rise in blood glucose is met with an appropriate insulin response, while also trimming hepatic glucose production through glucagon suppression. Slower gastric emptying and reduced appetite further help to blunt post-meal glucose excursions and support weight management.

– In people with type 2 diabetes, the incretin effect may be reduced or dysregulated. Therapies that enhance GLP-1 activity—either by providing GLP-1–like stimulation or by preserving endogenous GLP-1—aim to restore a more physiologic post-meal glucose control.

– GLP-1–based strategies are part of a broader approach to diabetes care that includes diet, physical activity, and other glucose-lowering medications. Individual responses vary, so treatment choices are tailored to each person’s needs, preferences, and risk profile.

In short, GLP-1 is a gut-derived hormone that coordinates the post-meal glucose response by boosting insulin secretion when glucose is high, suppressing glucagon, slowing digestion, and curbing appetite. These actions—especially when harnessed by modern therapies—help improve blood sugar control and can support weight loss and cardiovascular health in people with metabolic disease.